History is an inexact science to be sure, relying at least partially on hearsay and filtered through the political whims of its era. History is also old in the physical sense of the word, an unattractive quality to some.

But the past isn’t dead. As William Faulkner said, “it isn’t even past.”

Yes, the actors are gone, places have closed or vanished. Attitudes and beliefs have also changed … but it is this sort of mental change that is the value of knowing history: to discover what fails, and what succeeds.

Yes, the actors are gone, places have closed or vanished. Attitudes and beliefs have also changed … but it is this sort of mental change that is the value of knowing history: to discover what fails, and what succeeds.

A society’s shared knowledge of history can be compared to a person’s memories. It would be a tragedy for an adult to lose the lessons of youth, to forget what happens when your hand meets a hot stove or a light socket. We could not expect an adult without memories of prior experience to prosper, or even to survive very long. Human society may be no different.

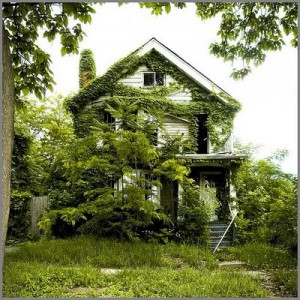

There is nothing inherently needful about human society on Earth: nature proceeds quite well without us. Mankind has the tendency to forget the value of cooperation and commonwealth and retreat to our primitive tribal tendencies as frightened creatures suffering Hobbesian lives–“nasty, brutish, short.” These cycles have been called “dark” ages, and these times of forgetting have occurred throughout human history. The “Middle Ages” are a recent example, a backward era that existed between antiquity’s civilization and our own. Human progress is not a straight line.

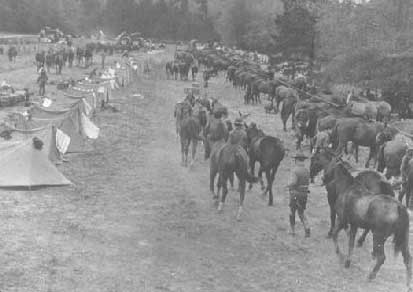

If mankind had never discovered fire, or the wheel, or horsemanship, or any of the multiplicity of specializations and customs and insights that make up civilized life–the forests and plains would be there, the world would still turn.

Some may see the world today and mistake success for inevitability. But there is nothing inherently necessary about human civilization on Earth. There is no observable feature of nature to preserve us in our ignorance. We prosper by our hard-learned knowledge, but the cliff is always there to fall from if we forget.